Balfour Declaration

| Balfour Declaration | |

|---|---|

The original letter from Balfour to Rothschild; the declaration reads:

| |

| Created | 2 November 1917 |

| Location | British Library |

| Author(s) | Walter Rothschild, Arthur Balfour, Leo Amery, Lord Milner |

| Signatories | Arthur James Balfour |

| Purpose | Confirming support from the British government for the establishment in Palestine of a "national home" for the Jewish people, with two conditions |

| Full text | |

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population. The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917.

Immediately following Britain's declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, it began to consider the future of Palestine. Within two months a memorandum was circulated to the War Cabinet by a Zionist member, Herbert Samuel, proposing the support of Zionist ambitions in order to enlist the support of Jews in the wider war. A committee was established in April 1915 by British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith to determine their policy towards the Ottoman Empire including Palestine. Asquith, who had favoured post-war reform of the Ottoman Empire, resigned in December 1916; his replacement David Lloyd George favoured partition of the Empire. The first negotiations between the British and the Zionists took place at a conference on 7 February 1917 that included Sir Mark Sykes and the Zionist leadership. Subsequent discussions led to Balfour's request, on 19 June, that Rothschild and Chaim Weizmann submit a draft of a public declaration. Further drafts were discussed by the British Cabinet during September and October, with input from Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews but with no representation from the local population in Palestine.

By late 1917, in the lead-up to the Balfour Declaration, the wider war had reached a stalemate, with two of Britain's allies not fully engaged: the United States had yet to suffer a casualty, and the Russians were in the midst of a revolution with Bolsheviks taking over the government. A stalemate in southern Palestine was broken by the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917. The release of the final declaration was authorised on 31 October; the preceding Cabinet discussion had referenced perceived propaganda benefits amongst the worldwide Jewish community for the Allied war effort.

The opening words of the declaration represented the first public expression of support for Zionism by a major political power. The term "national home" had no precedent in international law, and was intentionally vague as to whether a Jewish state was contemplated. The intended boundaries of Palestine were not specified, and the British government later confirmed that the words "in Palestine" meant that the Jewish national home was not intended to cover all of Palestine. The second half of the declaration was added to satisfy opponents of the policy, who had claimed that it would otherwise prejudice the position of the local population of Palestine and encourage antisemitism worldwide by "stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands". The declaration called for safeguarding the civil and religious rights for the Palestinian Arabs, who composed the vast majority of the local population, and also the rights and political status of the Jewish communities in other countries outside of Palestine. The British government acknowledged in 1939 that the local population's wishes and interests should have been taken into account, and recognised in 2017 that the declaration should have called for the protection of the Palestinian Arabs' political rights.

The declaration had many long-lasting consequences. It greatly increased popular support for Zionism within Jewish communities worldwide, and became a core component of the British Mandate for Palestine, the founding document of Mandatory Palestine. It indirectly led to the emergence of the State of Israel and is considered a principal cause of the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict, often described as the world's most intractable conflict. Controversy remains over a number of areas, such as whether the declaration contradicted earlier promises the British made to the Sharif of Mecca in the McMahon–Hussein correspondence.

Background

Early British support

Early British political support for an increased Jewish presence in the region of Palestine was based upon geopolitical calculations.[1][i] This support began in the early 1840s[3] and was led by Lord Palmerston, following the occupation of Syria and Palestine by separatist Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[4][5] French influence had grown in Palestine and the wider Middle East, and its role as protector of the Catholic communities began to grow, just as Russian influence had grown as protector of the Eastern Orthodox in the same regions. This left Britain without a sphere of influence,[4] and thus a need to find or create their own regional "protégés".[6] These political considerations were supported by a sympathetic evangelical Christian sentiment towards the "restoration of the Jews" to Palestine among elements of the mid-19th-century British political elite – most notably Lord Shaftesbury.[ii] The British Foreign Office actively encouraged Jewish emigration to Palestine, exemplified by Charles Henry Churchill's 1841–1842 exhortations to Moses Montefiore, the leader of the British Jewish community.[8][a]

Such efforts were premature,[8] and did not succeed;[iii] only 24,000 Jews were living in Palestine on the eve of the emergence of Zionism within the world's Jewish communities in the last two decades of the 19th century.[10] With the geopolitical shakeup occasioned by the outbreak of the First World War, the earlier calculations, which had lapsed for some time, led to a renewal of strategic assessments and political bargaining over the Middle and Far East.[5]

British anti-Semitism

Although other factors played their part, Jonathan Schneer says that stereotypical thinking by British officials about Jews also played a role in the decision to issue the Declaration. Robert Cecil, Hugh O’Bierne and Sir Mark Sykes all held an unrealistic view of "world Jewry", the former writing "I do not think it is possible to exaggerate the international power of the Jews." Zionist representatives saw advantage in encouraging such views.[11][12] James Renton concurs, writing that the British foreign policy elite, including Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Foreign Secretary A.J. Balfour, believed that Jews possessed real and significant power that could be of use to them in the war.[13]

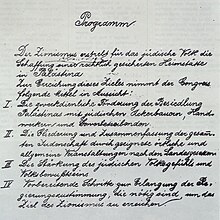

Early Zionism

Zionism arose in the late 19th century in reaction to anti-Semitic and exclusionary nationalist movements in Europe.[14][iv][v] Romantic nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe had helped to set off the Haskalah, or "Jewish Enlightenment", creating a split in the Jewish community between those who saw Judaism as their religion and those who saw it as their ethnicity or nation.[14][15] The 1881–1884 anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire encouraged the growth of the latter identity, resulting in the formation of the Hovevei Zion pioneer organizations, the publication of Leon Pinsker's Autoemancipation, and the first major wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine – retrospectively named the "First Aliyah".[17][18][15]

In 1896, Theodor Herzl, a Jewish journalist living in Austria-Hungary, published the foundational text of political Zionism, Der Judenstaat ("The Jews' State" or "The State of the Jews"), in which he asserted that the only solution to the "Jewish Question" in Europe, including growing anti-Semitism, was the establishment of a state for the Jews.[19][20] A year later, Herzl founded the Zionist Organization, which at its first congress called for the establishment of "a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law". Proposed measures to attain that goal included the promotion of Jewish settlement there, the organisation of Jews in the diaspora, the strengthening of Jewish feeling and consciousness, and preparatory steps to attain necessary governmental grants.[20] Herzl died in 1904, 44 years before the establishment of State of Israel, the Jewish state that he proposed, without having gained the political standing required to carry out his agenda.[10]

Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, later President of the World Zionist Organisation and first President of Israel, moved from Switzerland to the UK in 1904 and met Arthur Balfour – who had just launched his 1905–1906 election campaign after resigning as Prime Minister[21] – in a session arranged by Charles Dreyfus, his Jewish constituency representative.[vi] Earlier that year, Balfour had successfully driven the Aliens Act through Parliament with impassioned speeches regarding the need to restrict the wave of immigration into Britain from Jews fleeing the Russian Empire.[23][24] During this meeting, he asked what Weizmann's objections had been to the 1903 Uganda Scheme that Herzl had supported to provide a portion of British East Africa to the Jewish people as a homeland. The scheme, which had been proposed to Herzl by Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary in Balfour's Cabinet, following his trip to East Africa earlier in the year,[vii] had been subsequently voted down following Herzl's death by the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905[viii] after two years of heated debate in the Zionist Organization.[27] Weizmann responded that he believed the English are to London as the Jews are to Jerusalem.[b]

In January 1914 Weizmann first met Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a member of the French branch of the Rothschild family and a leading proponent of the Zionist movement,[29] in relation to a project to build a Hebrew university in Jerusalem.[29] The Baron was not part of the World Zionist Organization, but had funded the Jewish agricultural colonies of the First Aliyah and transferred them to the Jewish Colonization Association in 1899.[30] This connection was to bear fruit later that year when the Baron's son, James de Rothschild, requested a meeting with Weizmann on 25 November 1914, to enlist him in influencing those deemed to be receptive within the British government to their agenda of a "Jewish State" in Palestine.[c][32] Through James's wife Dorothy, Weizmann was to meet Rózsika Rothschild, who introduced him to the English branch of the family – in particular her husband Charles and his older brother Walter, a zoologist and former Member of Parliament (MP).[33] Their father, Nathan Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild, head of the English branch of the family, had a guarded attitude towards Zionism, but he died in March 1915 and his title was inherited by Walter.[33][34]

Prior to the declaration, about 8,000 of Britain's 300,000 Jews belonged to a Zionist organisation.[35][36] Globally, as of 1913 – the latest known date prior to the declaration – the equivalent figure was approximately 1%.[37]

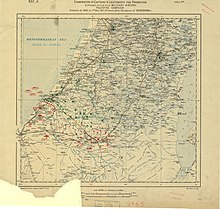

Ottoman Palestine

Published in 1732, this map by Ottoman geographer Kâtip Çelebi (1609–57) shows the term ارض فلسطين (ʾarḍ Filasṭīn, "Land of Palestine") extending vertically down the length of the Jordan River.[38]

|

The year 1916 marked four centuries since Palestine had become part of the Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire.[39] For most of this period, the Jewish population represented a small minority, approximately 3% of the total, with Muslims representing the largest segment of the population, and Christians the second.[40][41][42][ix]

Ottoman government in Constantinople began to apply restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine in late 1882, in response to the start of the First Aliyah earlier that year.[44] Although this immigration was creating a certain amount of tension with the local population, mainly among the merchant and notable classes, in 1901 the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman central government) gave Jews the same rights as Arabs to buy land in Palestine and the percentage of Jews in the population rose to 7% by 1914.[45] At the same time, with growing distrust of the Young Turks (Turkish nationalists who had taken control of the Empire in 1908) and the Second Aliyah, Arab nationalism and Palestinian nationalism was on the rise; and in Palestine anti-Zionism was a characteristic that unified these forces.[45][46] Historians do not know whether these strengthening forces would still have ultimately resulted in conflict in the absence of the Balfour Declaration.[x]

First World War

1914–16: Initial Zionist–British Government discussions

In July 1914 war broke out in Europe between the Triple Entente (Britain, France, and the Russian Empire) and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and, later that year, the Ottoman Empire).[48]

The British Cabinet first discussed Palestine at a meeting on 9 November 1914, four days after Britain's declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire, of which the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem – often referred to as Palestine[49] – was a component. At the meeting David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, "referred to the ultimate destiny of Palestine".[50] The Chancellor, whose law firm Lloyd George, Roberts and Co had been engaged a decade before by the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland to work on the Uganda Scheme,[51] was to become Prime Minister by the time of the declaration, and was ultimately responsible for it.[52]

Weizmann's political efforts picked up speed,[d] and on 10 December 1914 he met with Herbert Samuel, a British Cabinet member and a secular Jew who had studied Zionism;[54] Samuel believed Weizmann's demands were too modest.[e] Two days later, Weizmann met Balfour again, for the first time since their initial meeting in 1905; Balfour had been out of government ever since his electoral defeat in 1906, but remained a senior member of the Conservative Party in their role as Official Opposition.[f]

A month later, Samuel circulated a memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine to his Cabinet colleagues. The memorandum stated: "I am assured that the solution of the problem of Palestine which would be much the most welcome to the leaders and supporters of the Zionist movement throughout the world would be the annexation of the country to the British Empire".[57] Samuel discussed a copy of his memorandum with Nathan Rothschild in February 1915, a month before the latter's death.[34] It was the first time in an official record that enlisting the support of Jews as a war measure had been proposed.[58]

Many further discussions followed, including the initial meetings in 1915–16 between Lloyd George, who had been appointed Minister of Munitions in May 1915,[59] and Weizmann, who was appointed as a scientific advisor to the ministry in September 1915.[60][59] Seventeen years later, in his War Memoirs, Lloyd George described these meetings as being the "fount and origin" of the declaration; historians have rejected this claim.[g]

1915–16: Prior British commitments over Palestine

In late 1915 the British High Commissioner to Egypt, Henry McMahon, exchanged ten letters with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, in which he promised Hussein to recognize Arab independence "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca" in return for Hussein launching a revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The pledge excluded "portions of Syria" lying to the west of "the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo".[68][h] In the decades after the war, the extent of this coastal exclusion was hotly disputed[70] since Palestine lay to the southwest of Damascus and was not explicitly mentioned.[68]

The Arab Revolt was launched on June 5th, 1916,[73] on the basis of the quid pro quo agreement in the correspondence.[74] However, less than three weeks earlier the governments of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia secretly concluded the Sykes–Picot Agreement, which Balfour described later as a "wholly new method" for dividing the region, after the 1915 agreement "seems to have been forgotten".[j]

This Anglo-French treaty was negotiated in late 1915 and early 1916 between Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, with the primary arrangements being set out in draft form in a joint memorandum on 5 January 1916.[76][77] Sykes was a British Conservative MP who had risen to a position of significant influence on Britain's Middle East policy, beginning with his seat on the 1915 De Bunsen Committee and his initiative to create the Arab Bureau.[78] Picot was a French diplomat and former consul-general in Beirut.[78] Their agreement defined the proposed spheres of influence and control in Western Asia should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I,[79][80] dividing many Arab territories into British- and French-administered areas. In Palestine, internationalisation was proposed,[79][80] with the form of administration to be confirmed after consultation with both Russia and Hussein;[79] the January draft noted Christian and Muslim interests, and that "members of the Jewish community throughout the world have a conscientious and sentimental interest in the future of the country."[77][81][k]

Prior to this point, no active negotiations with Zionists had taken place, but Sykes had been aware of Zionism, was in contact with Moses Gaster – a former President of the English Zionist Federation[83] – and may have seen Samuel's 1915 memorandum.[81][84] On 3 March, while Sykes and Picot were still in Petrograd, Lucien Wolf (secretary of the Foreign Conjoint Committee, set up by Jewish organizations to further the interests of foreign Jews) submitted to the Foreign Office, the draft of an assurance (formula) that could be issued by the allies in support of Jewish aspirations:

In the event of Palestine coming within the spheres of influence of Great Britain or France at the close of the war, the governments of those powers will not fail to take account of the historic interest that country possesses for the Jewish community. The Jewish population will be secured in the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, equal political rights with the rest of the population, reasonable facilities for immigration and colonisation, and such municipal privileges in the towns and colonies inhabited by them as may be shown to be necessary.

On 11 March, telegrams[l] were sent in Grey's name to Britain's Russian and French ambassadors for transmission to Russian and French authorities, including the formula, as well as:

The scheme might be made far more attractive to the majority of Jews if it held out to them the prospect that when in course of time the Jewish colonists in Palestine grow strong enough to cope with the Arab population they may be allowed to take the management of the internal affairs of Palestine (with the exception of Jerusalem and the holy places) into their own hands.

Sykes, having seen the telegram, had discussions with Picot and proposed (making reference to Samuel's memorandum[m]) the creation of an Arab Sultanate under French and British protection, some means of administering the holy places along with the establishment of a company to purchase land for Jewish colonists, who would then become citizens with equal rights to Arabs.[n]

Shortly after returning from Petrograd, Sykes briefed Samuel, who then briefed a meeting of Gaster, Weizmann and Sokolow. Gaster recorded in his diary on 16 April 1916: "We are offered French-English condominium in Palest[ine]. Arab Prince to conciliate Arab sentiment and as part of the Constitution a Charter to Zionists for which England would stand guarantee and which would stand by us in every case of friction ... It practically comes to a complete realisation of our Zionist programme. However, we insisted on: national character of Charter, freedom of immigration and internal autonomy, and at the same time full rights of citizenship to [illegible] and Jews in Palestine."[86] In Sykes' mind, the agreement which bore his name was outdated even before it was signed – in March 1916, he wrote in a private letter: "to my mind the Zionists are now the key of the situation".[xii][88] In the event, neither the French nor the Russians were enthusiastic about the proposed formulation and eventually on 4 July, Wolf was informed that "the present moment is inopportune for making any announcement."[89]

These wartime initiatives, inclusive of the declaration, are frequently considered together by historians because of the potential, real or imagined, for incompatibility between them, particularly in regard to the disposition of Palestine.[90] In the words of Professor Albert Hourani, founder of the Middle East Centre at St Antony's College, Oxford: "The argument about the interpretation of these agreements is one which is impossible to end, because they were intended to bear more than one interpretation."[91]

1916–17: Change in British Government

In terms of British politics, the declaration resulted from the coming into power of Lloyd George and his Cabinet, which had replaced the H. H. Asquith led-Cabinet in December 1916. Whilst both Prime Ministers were Liberals and both governments were wartime coalitions, Lloyd George and Balfour, appointed as his Foreign Secretary, favoured a post-war partition of the Ottoman Empire as a major British war aim, whereas Asquith and his Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had favoured its reform.[92][93]

Two days after taking office, Lloyd George told General Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, that he wanted a major victory, preferably the capture of Jerusalem, to impress British public opinion,[94] and immediately consulted his War Cabinet about a "further campaign into Palestine when El Arish had been secured."[95] Subsequent pressure from Lloyd George, over the reservations of Robertson, resulted in the recapture of the Sinai for British-controlled Egypt, and, with the capture of El Arish in December 1916 and Rafah in January 1917, the arrival of British forces at the southern borders of the Ottoman Empire.[95] Following two unsuccessful attempts to capture Gaza between 26 March and 19 April, a six-month stalemate in Southern Palestine began;[96] the Sinai and Palestine Campaign would not make any progress into Palestine until 31 October 1917.[97]

1917: British-Zionist formal negotiations

Following the change in government, Sykes was promoted into the War Cabinet Secretariat with responsibility for Middle Eastern affairs. In January 1917, despite having previously built a relationship with Moses Gaster,[xiii] he began looking to meet other Zionist leaders; by the end of the month he had been introduced to Weizmann and his associate Nahum Sokolow, a journalist and executive of the World Zionist Organization who had moved to Britain at the beginning of the war.[xiv]

On 7 February 1917, Sykes, claiming to be acting in a private capacity, entered into substantive discussions with the Zionist leadership.[o] The previous British correspondence with "the Arabs" was discussed at the meeting; Sokolow's notes record Sykes' description that "The Arabs professed that language must be the measure [by which control of Palestine should be determined] and [by that measure] could claim all Syria and Palestine. Still the Arabs could be managed, particularly if they received Jewish support in other matters."[100][101][p] At this point the Zionists were still unaware of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, although they had their suspicions.[100] One of Sykes' goals was the mobilization of Zionism to the cause of British suzerainty in Palestine, so as to have arguments to put to France in support of that objective.[103]

Late 1917: Progress of the wider war

During the period of the British War Cabinet discussions leading up to the declaration, the war had reached a period of stalemate. On the Western Front the tide would first turn in favour of the Central Powers in spring 1918,[104] before decisively turning in favour of the Allies from July 1918 onwards.[104] Although the United States declared war on Germany in the spring of 1917, it did not suffer its first casualties until 2 November 1917,[105] at which point President Woodrow Wilson still hoped to avoid dispatching large contingents of troops into the war.[106] The Russian forces were known to be distracted by the ongoing Russian Revolution and the growing support for the Bolshevik faction, but Alexander Kerensky's Provisional Government had remained in the war; Russia only withdrew after the final stage of the revolution on 7 November 1917.[107]

Approvals

April to June: Allied discussions

Balfour met Weizmann at the Foreign Office on 22 March 1917; two days later, Weizmann described the meeting as being "the first time I had a real business talk with him".[108] Weizmann explained at the meeting that the Zionists had a preference for a British protectorate over Palestine, as opposed to an American, French or international arrangement; Balfour agreed, but warned that "there may be difficulties with France and Italy".[108]

The French position in regard to Palestine and the wider Syria region during the lead up to the Balfour Declaration was largely dictated by the terms of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and was complicated from 23 November 1915 by increasing French awareness of the British discussions with the Sherif of Mecca.[109] Prior to 1917, the British had led the fighting on the southern border of the Ottoman Empire alone, given their neighbouring Egyptian colony and the French preoccupation with the fighting on the Western Front that was taking place on their own soil.[110][111] Italy's participation in the war, which began following the April 1915 Treaty of London, did not include involvement in the Middle Eastern sphere until the April 1917 Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne; at this conference, Lloyd George had raised the question of a British protectorate of Palestine and the idea "had been very coldly received" by the French and the Italians.[112][113][q] In May and June 1917, the French and Italians sent detachments to support the British as they built their reinforcements in preparation for a renewed attack on Palestine.[110][111]

In early April, Sykes and Picot were appointed to act as the chief negotiators once more, this time on a month-long mission to the Middle East for further discussions with the Sherif of Mecca and other Arab leaders.[114][r] On 3 April 1917, Sykes met with Lloyd George, Lord Curzon and Maurice Hankey to receive his instructions in this regard, namely to keep the French onside while "not prejudicing the Zionist movement and the possibility of its development under British auspices, [and not] enter into any political pledges to the Arabs, and particularly none in regard to Palestine".[116] Before travelling to the Middle East, Picot, via Sykes, invited Nahum Sokolow to Paris to educate the French government on Zionism.[117] Sykes, who had prepared the way in correspondence with Picot,[118] arrived a few days after Sokolow; in the meantime, Sokolow had met Picot and other French officials, and convinced the French Foreign Office to accept for study a statement of Zionist aims "in regard to facilities of colonization, communal autonomy, rights of language and establishment of a Jewish chartered company."[119] Sykes went on ahead to Italy and had meetings with the British ambassador and British Vatican representative to prepare the way for Sokolow once again.[120]

Sokolow was granted an audience with Pope Benedict XV on 6 May 1917.[121] Sokolow's notes of the meeting – the only meeting records known to historians – stated that the Pope expressed general sympathy and support for the Zionist project.[122][xv] On 21 May 1917 Angelo Sereni, president of the Committee of the Jewish Communities,[s] presented Sokolow to Sidney Sonnino, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was also received by Paolo Boselli, the Italian prime minister. Sonnino arranged for the secretary general of the ministry to send a letter to the effect that, although he could not express himself on the merits of a program which concerned all the allies, "generally speaking" he was not opposed to the legitimate claims of the Jews.[128] On his return journey, Sokolow met with French leaders again and secured a letter dated 4 June 1917, giving assurances of sympathy towards the Zionist cause by Jules Cambon, head of the political section of the French foreign ministry.[129] This letter was not published, but was deposited at the British Foreign Office.[130][xvi]

Following the United States' entry into the war on 6 April, the British Foreign Secretary led the Balfour Mission to Washington, D.C., and New York, where he spent a month between mid-April and mid-May. During the trip he spent significant time discussing Zionism with Louis Brandeis, a leading Zionist and a close ally of Wilson who had been appointed as a Supreme Court Justice a year previously.[t]

June and July: Decision to prepare a declaration

By 13 June 1917, it was acknowledged by Ronald Graham, head of the Foreign Office's Middle Eastern affairs department, that the three most relevant politicians – the Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary, and the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Robert Cecil – were all in favour of Britain supporting the Zionist movement;[u] on the same day Weizmann had written to Graham to advocate for a public declaration.[v][134][135]

Six days later, at a meeting on 19 June, Balfour asked Lord Rothschild and Weizmann to submit a formula for a declaration.[136] Over the next few weeks, a 143-word draft was prepared by the Zionist negotiating committee, but it was considered too specific on sensitive areas by Sykes, Graham and Rothschild.[137] Separately, a very different draft had been prepared by the Foreign Office, described in 1961 by Harold Nicolson – who had been involved in preparing the draft – as proposing a "sanctuary for Jewish victims of persecution".[138][139] The Foreign Office draft was strongly opposed by the Zionists, and was discarded; no copy of the draft has been found in the Foreign Office archives.[138][139]

Following further discussion, a revised – and at just 46 words in length, much shorter – draft declaration was prepared and sent by Lord Rothschild to Balfour on 18 July.[137] It was received by the Foreign Office, and the matter was brought to the Cabinet for formal consideration.[140]

September and October: American consent and War Cabinet approval

The decision to release the declaration was taken by the British War Cabinet on 31 October 1917. This followed discussion at four War Cabinet meetings (including the 31 October meeting) over the space of the previous two months.[140] In order to aid the discussions, the War Cabinet Secretariat, led by Maurice Hankey, the Cabinet Secretary and supported by his Assistant Secretaries[141][142] – primarily Sykes and his fellow Conservative MP and pro-Zionist Leo Amery – solicited outside perspectives to put before the Cabinet. These included the views of government ministers, war allies – notably from President Woodrow Wilson – and in October, formal submissions from six Zionist leaders and four non-Zionist Jews.[140]

British officials asked President Wilson for his consent on the matter on two occasions – first on 3 September, when he replied the time was not ripe, and later on 6 October, when he agreed with the release of the declaration.[143]

Excerpts from the minutes of these four War Cabinet meetings provide a description of the primary factors that the ministers considered:

- 3 September 1917: "With reference to a suggestion that the matter might be postponed, [Balfour] pointed out that this was a question on which the Foreign Office had been very strongly pressed for a long time past. There was a very strong and enthusiastic organisation, more particularly in the United States, who were zealous in this matter, and his belief was that it would be of most substantial assistance to the Allies to have the earnestness and enthusiasm of these people enlisted on our side. To do nothing was to risk a direct breach with them, and it was necessary to face this situation."[144]

- 4 October 1917: "... [Balfour] stated that the German Government were making great efforts to capture the sympathy of the Zionist Movement. This Movement, though opposed by a number of wealthy Jews in this country, had behind it the support of a majority of Jews, at all events in Russia and America, and possibly in other countries ... Mr. Balfour then read a very sympathetic declaration by the French Government which had been conveyed to the Zionists, and he stated that he knew that President Wilson was extremely favourable to the Movement."[145]

- 25 October 1917: "... the Secretary mentioned that he was being pressed by the Foreign Office to bring forward the question of Zionism, an early settlement of which was regarded as of great importance."[146]

- 31 October 1917: "[Balfour] stated that he gathered that everyone was now agreed that, from a purely diplomatic and political point of view, it was desirable that some declaration favourable to the aspirations of the Jewish nationalists should now be made. The vast majority of Jews in Russia and America, as, indeed, all over the world, now appeared to be favourable to Zionism. If we could make a declaration favourable to such an ideal, we should be able to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and America."[147]

Drafting

Declassification of British government archives has allowed scholars to piece together the choreography of the drafting of the declaration; in his widely cited 1961 book, Leonard Stein published four previous drafts of the declaration.[148]

The drafting began with Weizmann's guidance to the Zionist drafting team on its objectives in a letter dated 20 June 1917, one day following his meeting with Rothschild and Balfour. He proposed that the declaration from the British government should state: "its conviction, its desire or its intention to support Zionist aims for the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine; no reference must be made I think to the question of the Suzerain Power because that would land the British into difficulties with the French; it must be a Zionist declaration."[92][149]

A month after the receipt of the much-reduced 12 July draft from Rothschild, Balfour proposed a number of mainly technical amendments.[148] The two subsequent drafts included much more substantial amendments: the first in a late August draft by Lord Milner – one of the original five members of Lloyd George's War Cabinet as a minister without portfolio[xvii] – which reduced the geographic scope from all of Palestine to "in Palestine", and the second from Milner and Amery in early October, which added the two "safeguard clauses".[148]

| List of known drafts of the Balfour Declaration, showing changes between each draft | ||

|---|---|---|

| Draft | Text | Changes |

| Preliminary Zionist draft July 1917[150] |

His Majesty's Government, after considering the aims of the Zionist Organization, accepts the principle of recognizing Palestine as the National Home of the Jewish people and the right of the Jewish people to build up its national life in Palestine under a protection to be established at the conclusion of peace following upon the successful issue of the War. His Majesty's Government regards as essential for the realization of this principle the grant of internal autonomy to the Jewish nationality in Palestine, freedom of immigration for Jews, and the establishment of a Jewish National Colonizing Corporation for the resettlement and economic development of the country. |

|

| Lord Rothschild draft 12 July 1917[150] |

1. His Majesty's Government accepts the principle that Palestine should be reconstituted as the national home of the Jewish people. 2. His Majesty's Government will use its best endeavours to secure the achievement of this object and will discuss the necessary methods and means with the Zionist Organisation.[148] |

|